Someone asked recently if policies and frameworks are the same thing. The answer is a definite no. It’s a chicken and egg thing. A policy might be written which requires that a particular framework be developed or implemented. Or an element of a framework might proscribe that a policy be developed and applied.

Another area of confusion is around the difference between frameworks and models. Sometimes either term can be applied to the same concepts, but there is a difference. Here’s the full story.

In this article we look at what defines a framework and what differentiates frameworks from models. What are they and what might they be good for? We’ll try to determine the value of applying a framework or frameworks to the management of small organisations’ information systems, with particular regard to risk and cybersecurity management.

We’ll also touch on some popular management frameworks and look at how our approach to managing risk in small business is changing.

Cake

Ok, so this is a cake. Actually, it’s a very tasty solid-state cake.

And I’m a great chef. I’m an expert at baking great cakes. And my best mate, who created this cake, is also a great chef.

I’ve seen this cake. I know what it looks like, and I know what it should taste like. So now I want to make one myself. There are two paths I can take:

- I can just go for it. My years of experience and high level of skill in culinary practice should mean I can make a cake which is pretty close to the original.

- I can ask my friend for the recipe. There will probably still be some minor variations, caused by surface temperatures and the like, but this will also be pretty close to the original.

Which way should I go?

Models & Frameworks

So let’s talk about models, what they are, and what differentiates a model from a framework.

A model is something that is used to represent something else; typically used in place of the original. Physical models and conceptual models are the two main types of models. Of course, unlike the models in this image, we’re concerned with conceptual models. A conceptual model is a model that exists in one`s mind. It’s a theoretical construct that represents something, using a set of variables and the logical relationships between them (DifferenceBetween.com, 2013).

A model is abstract and intangible, whereas a framework is linked to comprehensible and specific work; my idea of the cake, versus my friend’s recipe.

A framework is an organized structure of ideas, concepts, and well… models, and other related objects. It can be used to describe those relationships and to be easily communicated to other people. It can also be applied to the concepts and practices involved in a project.

Software developers treat models and frameworks slightly differently, but hey, we won’t go there!

A Model

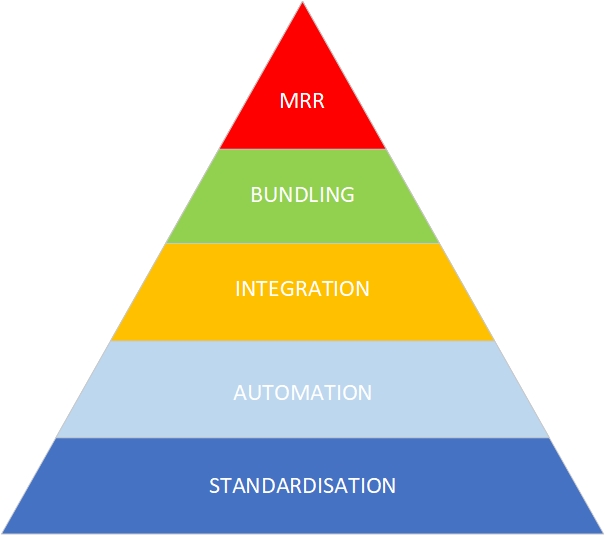

Above is the model our business is based on. We could call it the Baw Baw IT Managed Services Model, but it’s really a model all MSPs should be familiar with. Maybe they just haven’t conceptualised it quite the same.

The base of the model is standardisation: a standardised set of products, platforms and services is much easier to manage than a large, diverse, and fragmented set. Next is automation; we strive to automate our standardised platforms to increase efficiency, to be scalable, to get more done. To further increase our management efficiency, we want to integrate the management of our standardised, automated platforms. Imagine this as a ‘single pane of glass’; a single user interface or management console with one-click access to everything.

Integral to any managed services plan is the concept of bundling. The more of those standardised, automated, integrated products we can roll together into the customer’s ‘plan’, the more valuable that customer will be, the more valuable we are to the customer, and as proven by some of the major players (without mentioning any names), the ‘stickier’ the customer will be, i.e., less likely to churn to another provider. Sitting at the top of the pyramid is MRR, monthly recurring revenue, from a purely business perspective, the ‘raison d’etre’ of managed services. It’s the point at which we abandon the retrospective, hourly billing of the ‘break-fix’ service model, and embrace the pro-active, value-driven managed services model.

As an IT service provider that started out on the break-fix model, we think it’s a beautiful thing! Not just for the recurring revenue but also because we don’t like clients calling saying, “Help! It’s broken; come quickly and fix it”. That’s stress. We don’t want it, and the customer doesn’t want it. The model doesn’t just work better for us, it works better for our clients too.

As we built out our management systems, we worked the layers from bottom to top. Note however, that we could work this model in either direction, from the bottom to the top or from the top to the bottom, depending on our point of focus.

If we’re really focussed on our drivers, we need to start at the top, with the monthly recurring revenue, and work the model downwards, as we analyse the requirements to support MRR.

The key difference is that in the bottom-to-top view, we make assumptions about what is good or valuable. Our assumptions might be based on years of experience, accepted best practice or even notions of compliance, but they’re still assumptions. We’re just working with the model of the cake.

If we want to prove that the model works, we need to start with our primary objective, in this case MRR, and work downwards from that objective, examining all the dependencies. At each level we could develop a body of research to demonstrate that, for example, bundling of services supports optimal MRR, or that platform integration supports bundling.

But hey, we didn’t do that! We just built a model, an idea or ideal. Something that looks like what it represents. To develop it fully, using the top-down approach, we need a framework. Per the cake metaphor, we needed to develop a recipe, that can be used, with predictable results, time and time again.

We had to disassemble each of the layers of our managed services model and analyse the components. We have to audit, manage, monitor, support, report and audit again, repeatedly and continuously, at each layer, to demonstrate that the model supports our objective: the baked in goodness of monthly recurring revenue.

Another Model

So, here’s a different model: the Australian Signals Directorate’s Essential Eight (ACSC, 2022).

The E8 provides a baseline of configuration standards which when implemented, will block most cyber threats. According to Microsoft, multifactor authentication alone will block 99% of authentication exploits (Maynes, 2019). Conventional wisdom and agreed best practice tell us that implementing accepted best practice can do a lot to protect our clients’ and our own data and systems.

However, we know, for example, that users themselves are the main source of risk. Sure, we can tighten authentication mechanisms and restrict their privileges, but we need more. We need user awareness. We need training. Where’s that in the E8 model? And the risk of financial fraud when a criminal disguised as a ‘trusted partner’ convinces an employee to make a fraudulent payment. Where’s that in the E8 model? According to the ACSC, scenarios like this are extremely common (ACSC, n. d.).

Yes, it’s just a model. It’s a bottom-up approach and hey, bad stuff still happens! We can still get it (the recipe) wrong.

Oh No, Another Model!

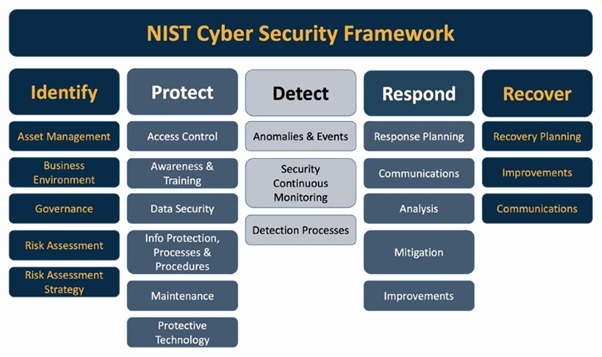

Which brings us to the NIST Cyber Security Framework (NIST, 2023). It looks pretty simple, right? Isn’t it just another model?

Well, yes, those five top-level activities might be a model, but then there are a bunch of further activities nested under each heading and a further seven steps (not shown here) for profiling, risk management and taking action (NIST, n. d.).

For every object in this diagram, NIST publishes a slew of Framework Profiles and Special Publications. Under the Protect category, for example, is NIST Special Publication 800-53, the 492 page, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations (NIST, 2020). It is a recommended reference for anyone tasked with managing cyber risks, but it’s just one of dozens of such documents.

In this model, it’s not so much a question of bottom-up or top-down. It’s about layers; how deep do we want to go. We could argue about where the model ends, and the framework begins. It doesn’t really matter.

Killchain

The diagram above shows the Lockheed Martin Cyber Killchain (Lockheed Martin, 2023). It’s a model which describes the progress of a typical cyberattack through an information system. Again, it’s just a model of the cake.

Of course, for a specific ingredient (malicious activity), we can investigate, analyse and develop each of the stages of the killchain. We can look at the vulnerabilities which enabled weaponisation and delivery, for example. We can look at the tactics, techniques and procedure employed by the malicious actors throughout the killchain. We could investigate the detailed interplay of cause and effect, resulting in the development of a framework to help us not only understand the means and method of attack, but also to help us defend our systems and data.

Mitre ATT&CK

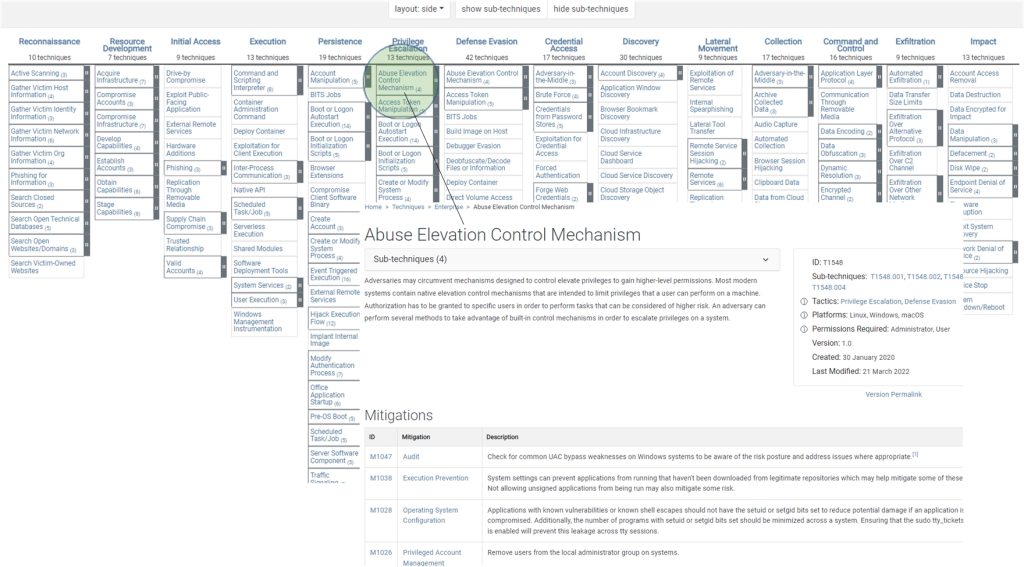

As we go deeper into the killchain, we might end up with something that looks like the Mitre ATT&CK Framework (Mitre, 2022). It describes the same progression as the Cyber Killchain, but with far greater detail and complexity.

Instead of seven stages, we now have fourteen stages, with nested attack vectors or exploits. We can drill into any of them to reveal details of the exploits, the sub-techniques attackers might use, and the steps needed to mitigate the risk of compromise.

Risk

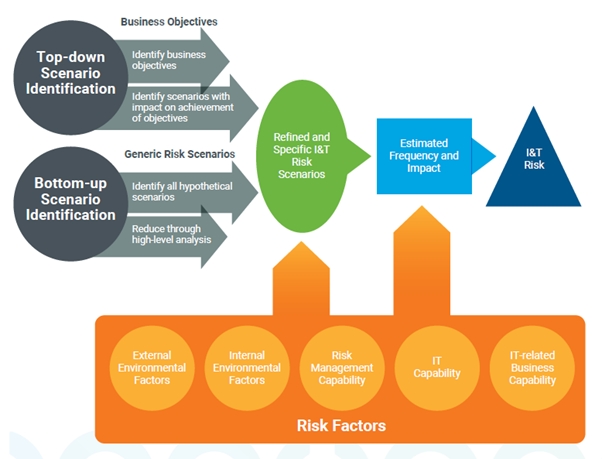

The diagram above shows a model of risk scenarios based on the ISACA risk management framework (ISACA, 2020).

The interesting thing about this diagram is that it highlights the point of this article. That is, that in general terms, there are two basic approaches to risk and cybersecurity management:

- Bottom-up, based on hypothetical scenarios. For example, we implement privilege management because we ‘know’ that someone will click on a malicious link or open a malicious email attachment. It relies on us as trusted advisors to tell our clients what must be done, and we do it, despite the frequent push-back, often from senior management who will fight for the right to retain admin privileges or not use MFA because it’s too inconvenient!

- But now we’re starting to see the need and the desire for robust cybersecurity coming down from the top, with the support of senior management, as in the top part of the diagram. This is driven by the objectives of the organisation, by its vision and mission, and demands the application of a framework, along with the development of policies and controls and systems for measurement and review.

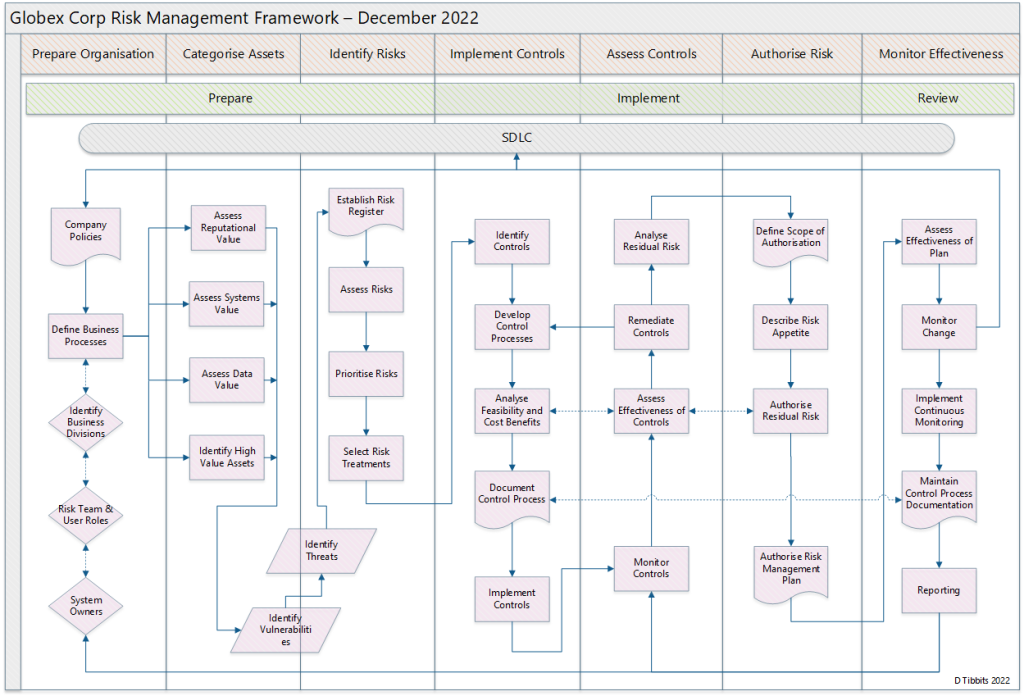

RMF

We’ve been providing IT services to small businesses long enough to remember when we were telling business owners that they could have a server on the premises; that servers weren’t just for big business. Later we told them about the cloud; that it wasn’t just for enterprise; that small businesses can, and should, go there too.

More recently we started talking to small businesses about risk management, and business continuity, areas of management that were foreign to them 10 years or so ago.

The point is, that as time goes by, technologies, management models and processes constantly filter down from enterprise to small business. In a sense, larger organisations test out these models and after they’ve been (somewhat) tried and tested, small businesses adopt them as a part of their constant quest for new ways to differentiate and compete. So, instead of taking a bottom-up approach to risk management, built on generalisations, they need to develop a more advanced, top-down risk management strategy as displayed in the risk management framework diagram above.

It’s not rocket science and it’s not as complex, or as costly as you might think. The risk of getting the recipe wrong, the mounting risk of a cyber incident, means that there can a very large cost benefit in getting it (recipe or framework) right.

References

Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) (2022). Essential Eight Maturity Model. Australian Government. https://www.cyber.gov.au/resources-business-and-government/essential-cyber-security/essential-eight/essential-eight-maturity-model

Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) (2023). Information Security Manual (ISM). Australian Government. https://www.cyber.gov.au/resources-business-and-government/essential-cyber-security/ism

Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) (n. d.). Preventing business email compromise. Australian Government. https://www.cyber.gov.au/protect-yourself/securing-your-email/email-security/preventing-business-email-compromise

Difference Between (2013, April). Difference Between Model and Framework. Difference Between. https://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-model-and-vs-framework/

ISACA (2020). IT Risk Framework. ISACA. https://store.isaca.org/s/store#/store/browse/detail/a2S4w000004KoZsEAK

Lockheed Martin (2023). The Cyber Kill Chain. Lockheed Martin. https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/cyber/cyber-kill-chain.html

Melanie Maynes (2019, August). One simple action you can take to prevent 99.9 percent of attacks on your accounts. Microsoft Corporation. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2019/08/20/one-simple-action-you-can-take-to-prevent-99-9-percent-of-account-attacks/

MITRE Corporation (Mitre) (2022). ATT&CK Matrix for Enterprise. The Mitre Corporation. https://attack.mitre.org/

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (2023). Cybersecurity Framework V1.1. NIST. https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework/framework

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (2018, December). SP 800-37 Rev. 2 – Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy. NIST. https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-37/rev-2/final

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (2011, March). SP 800-39 – Managing Information Security Risk: Organization, Mission, and Information System View. NIST. https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-39/final

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (2020, September). SP 800-53 Rev. 5 – Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations. NIST. https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/sp/800-53/rev-5/final

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) (n. d.). About the Risk Management Framework (RMF). NIST. https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/risk-management/about-rmf